Techies vs. the people that matter

In my last blog post, I described how the New York Times doesn’t cite technical experts, but rather “People Who Matter”—people with impressive résumés, like having been the “Director for Cyber Incident Response at the U.S. National Security Council at the White House”, the sort of person who speaks at the World Economic Forum in Davos on cybersecurity.

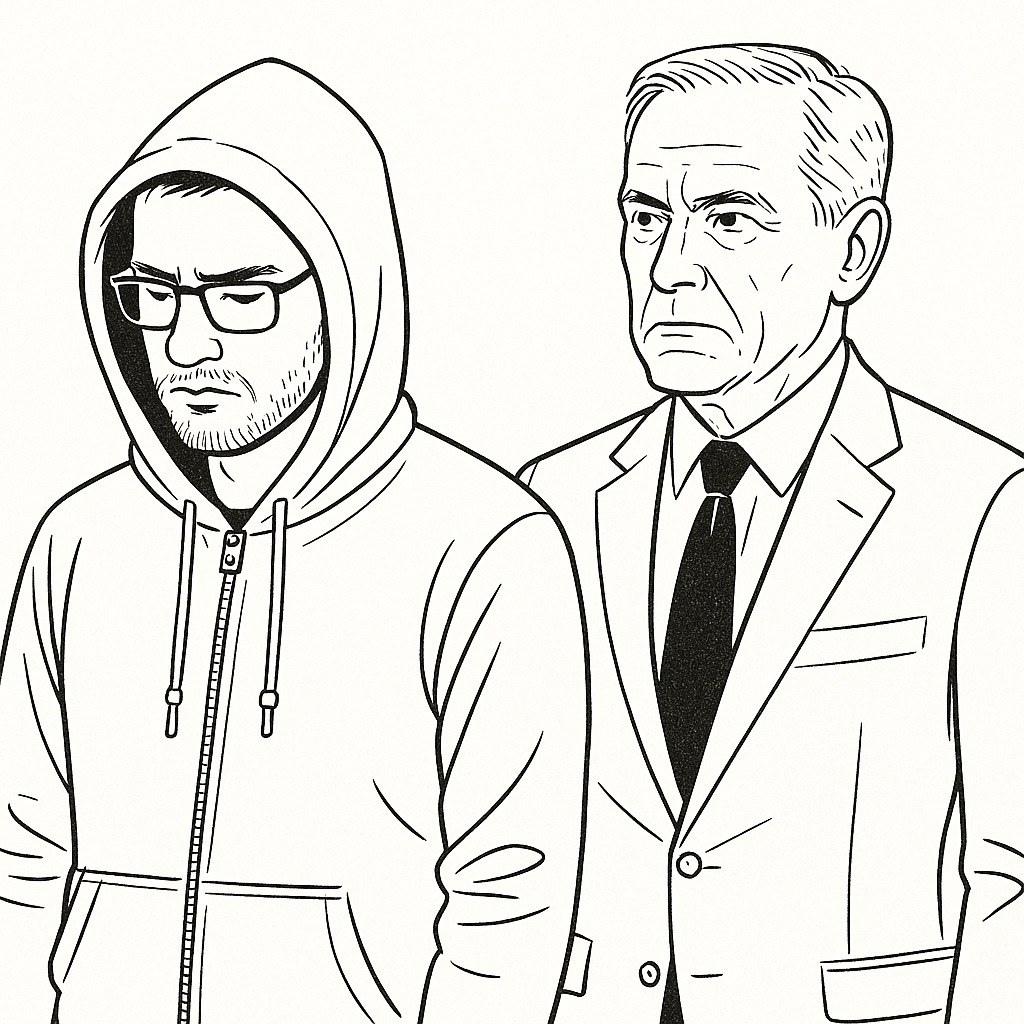

In this blog post, I double down on this claim, pitting myself (a techy) against Anthony J. Ferrante, the Person Who Matters quoted by the New York Times on yesterday’s UN SIM farm story, who has also been at the center of other stories.

This is the same guy who five years ago did forensics on Jeff Bezos’s iPhone to conclude that Saudi Crown Prince MBS had hacked Bezos. This was widely covered in the press and is generally assumed to be true.

But as a techy, I know the forensics analysis to be flawed. The forensics did not find a “smoking gun” to prove this—they only found unexplained anomalies. That’s a common flaw among forensics people, where anomalies become confirmation bias, where anything unexplained is used to support a foregone conclusion.

In particular, Ferrante’s team was unable to decrypt the video file sent by Saudi Crown Prince MBS to Bezos, the one they assumed contained malware.

They couldn’t decrypt the video due to lack of technical expertise. The file was end-to-end encrypted with WhatsApp. End-to-end means that nobody in the middle could decrypt the file, not even Facebook’s WhatsApp service itself. However, if you had one of the phones on either end, then you could decrypt it. Bezos’s iPhone had the decryption key—techies just needed to know where to find it.

The tools Ferrante used (like Cellebrite) are well known and respected in the forensics industry, but the tools didn’t have the ability to automatically decrypt WhatsApp. Forensics people are usually only trained on using tools effectively, not on how such things work underneath. When the tool doesn’t do it, they can’t do it themselves. Hence, they couldn’t decrypt the file.

In a blog post I wrote at the time, I described in great detail how techies can decrypt the file. I sent the same video to myself, performed forensics on my iPhone, then described step-by-step how to find the decryption key and decrypt it. I wrote code to help. Any competent forensics techy can follow the instructions and do the same.

Ferrante’s team could have done this and could have conclusively proven malware if it was there. But they didn’t have the knowledge. Instead, they had to rely upon guesses, using unexplained anomalies for their conclusions.

One of the anomalies was that the encrypted file was slightly larger than the original video, by 14 bytes. Ferrante attributed the difference to malware code. As my techy blog post explains, this is an artifact of encryption, which prepends a 10-byte “authentication code” on the front and appends 4 bytes of “padding” on the end. The reason for the anomaly is conclusively explained—the file was exactly the size it was supposed to be. If there were malware code inside, it was carefully constructed to be the same size.

The biggest unexplained anomaly was network traffic. Soon after the message from Saudi Crown Prince MBS was received, the phone appeared to send out bulk data, as if it were stealing all the photos and messages on the phone.

As another of my blog posts explains, such anomalous traffic is normal for Apple iPhones. They don’t smoothly log how much is being transmitted day by day. Instead, they can keep track of traffic for months and then create a single log entry with a large number. That’s what my Uber app did—slowly uploaded data (likely location information) day by day for months, and then the day I closed the app, reported 56 megabytes of upload.

This doesn’t conclusively explain the anomaly Ferrante’s team saw, but it does demonstrate that their conclusions aren’t really warranted. Abnormal iPhone traffic is, well, normal. This is the typical confirmation bias that plagues forensics.

I’m not claiming Ferrante and his team are incompetent. They delivered the standard results you get from standard forensics, which were inconclusive. Their conclusions were unwarranted, but that’s what the client wanted. The client wanted reasons to blame Saudi Crown Prince MBS.

My skills here are pretty rare. You wouldn’t expect the average forensics team to have known them. But they aren’t that rare. There are plenty of small, boutique firms that could have done this, but they are run by techies. They aren’t run by People Who Matter, like former members of the FBI and National Security Council. A billionaire like Bezos only wants People Who Matter, so wouldn’t get such techies.

The New York Times is a paper by the (self-appointed) elite for the elite. Their readers expect to hear from those with pedigrees, with FBI, Security Council, and WEF credentials. They don’t care how impressive a techy GitHub account is (mine is very impressive, by the way)—techies don’t matter. If techies had something useful to say, they’d tell their manager, who’d tell their manager, who’d tell the CEO or VP, who’d then get quoted in the New York Times.

As a result, you get these stories from the New York Times that aren’t about truth, but narratives. Bezos and his security chief Gavin de Becker wanted a story about Saudi MBS hacking. The Security Service wanted a story about how they foiled a plot against the UN. They matter, so their stories matter—even if I, as a techy, know them to be bogus.

Well put, my good man

Great post. I love your commentary. Neal Krawetz from the Hacker Factor blog is another example of a real techie. He only writes about stuff that he deeply understands.