Notes on yesterday $5 million judgement against Mike Lindell

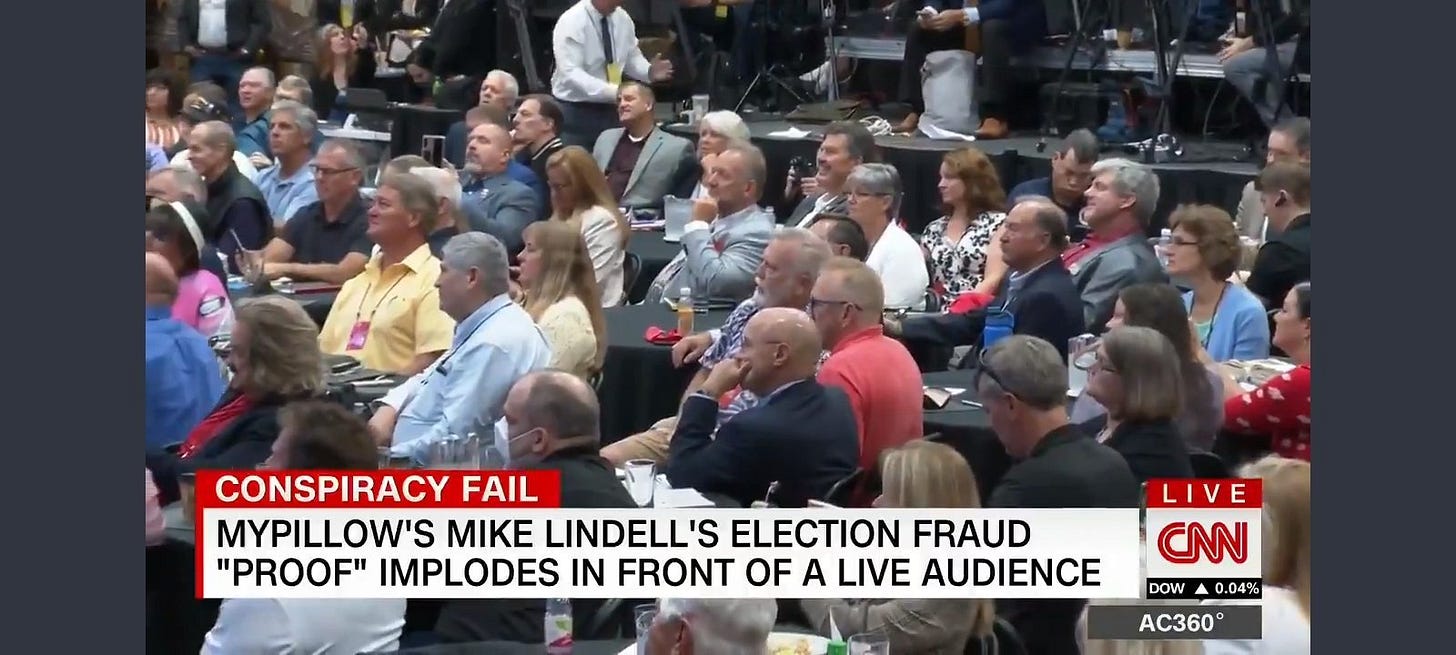

Yesterday, an arbitration panel ruled against Mike Lindell, ordering him to pay $5 million to a winner of his “Prove me Wrong” contest, for proving him wrong. Since I attended the cybersymposium, and could’ve won the contest, I thought I’d write up some notes.

An un-winnable contest

This story comes from Lindell’s 2021 “Cybersymposium” where he promised to release “pcaps” proving hackers flipped votes in the 2020 Presidential election. He offered the prize to anybody who provde that the data wasn’t from the 2020 election. I attended the Cybersymposium, but I did not apply for the prize. The reason is that I thought this contest was un-winnable.

Lindell provided some data, but it was incomprehensible. It’s like an encrypted ZIP file: it could contain anything. Without the password, nobody can prove what it does or does not contain.

Even though there’s no reason to believe it did contain data from the 2020 election, the rules where to prove it didn’t. You can’t prove a negative. It’s a rigged contest, so I didn’t bother.

The arbitration panel believed otherwise. I’m not sure I understand their reasoning. It sounds like that if they interpret the rules strictly, then it’s obvious the contest is rigged, and that’s fraud. Therefore, it seems, they were a little more relaxed, demanding that Lindell show some reason to believe any of the data was election related. Since there was no evidence, they found in favor of the cyberexpert.

The news stories on this event use language like the “computer software expert who disproved his false election claims”. That’s not true. The arbitration panel ruled in favor of the expert, but Lindell’s claims are still not proven wrong. They remain simply unsubstantiated — Lindell has never shown any reason to believe his claims, not even the smallest shred of evidence. They are almost certainly false, but still not provably false.

In retrospect, I should’ve entered the contest and pushed the issue. Even if Lindell makes an un-winnable contest, the law or an arbitration panel might have more wiggle room.

A hapless Lindell

Lindell is a charismatic, likable, and sincere guy. But I imagine he behaves in private the way he does in interviews with the press, badgering people to agree with him. Lindell keeps claiming his cyberguys have confirmed the data is real. But he seems to have surrounded himself with yes men, people with little technical skills that he can badgering into agreeing with what he wants to believe.

We see this in the decision. His side lost mostly because they were completely incompetent. He has no election data, but he hires people who tell him he’s got election data. You can see how this handicaps his side.

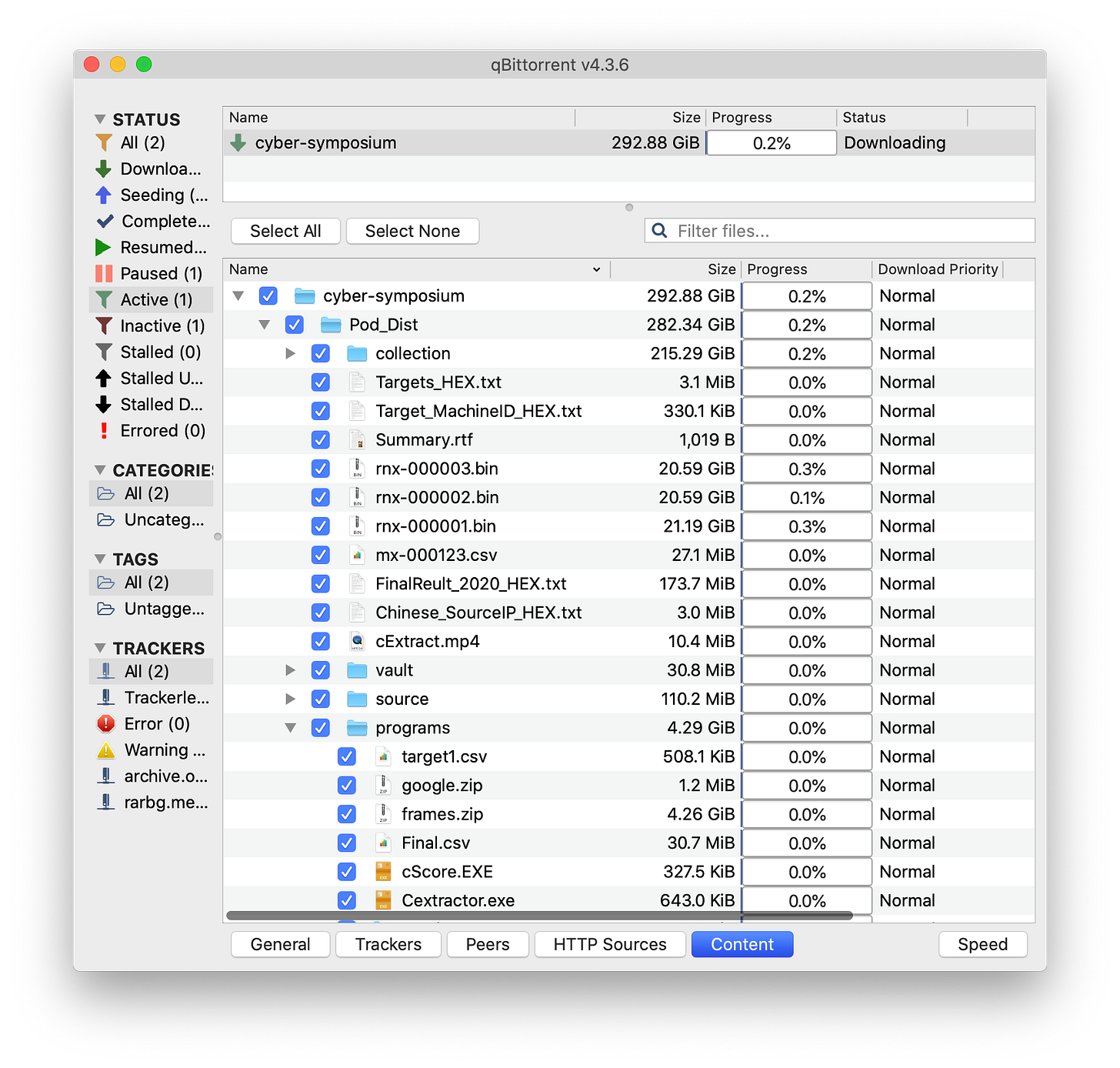

The decision lists the files given to the cyberexpert — but it’s an incomplete list. I was given a lot more files. They are public. Anybody can download them from the dark web with the BitTorrent link magnet:?xt=urn:btih:39a9590de21e77687fdf7eacee4dd743f2683d72&dn=cyber-symposium&tr=udp://9.rarbg.me:2780/announce.

Anybody (like Lindell supporters) can download this data and point to anything that could be 2020 election data, and thus refute the arbitration panel’s decision. I urge you to try — I’ll happily champion and publish what you find. It’s just that I couldn’t find it.

Lindell could have contested the decision by simply pointing out they gave more data to the cyberexperts than this cyberexpert analyzed. Lindell never made that argument because nobody has a clue which data was provided to the cyberexperts, least of all Lindell.

It was a Kafka-esque event. In Kafka’s story The Trial, “a man [is] arrested and prosecuted by a remote, inaccessible authority, with the nature of his crime revealed neither to him nor to the reader”.

The data in question comes from a Dennis Montgomery, a guy who has been peddling such conspiracy theories for years. I think Lindell expected Montgomery to come and present his data to the cyberexperts, to defend it against challengers. But Montgomery claimed to have a medical emergency, and didn’t come. It’s apparently an excuse he’s used in the past to get out of court appearances and such.

Lindell’s own people didn’t have a clue. His chief cyberguy was Phil Waldron, a former colonel in Army Intelligence. But he turned out to have no technical skills, and couldn’t answer basic questions other than confirm the data came from Montgomery. Waldron pointed to a second guy, Joshua Merritt, as the actual technical expert. Merritt had technical skills, but admitted to us that without Montgomery, nobody on Lindell’s team knew anything about what’s going on. He admitted that as far as he could tell, Montgomery’s data was bogus.

A reporter overheard Merritt saying this, reported this publicly in the Washington Times, after which Merritt disappeared from the conference the morning of the second day. We had little contact with either Waldron or Merritt on the first day, and no contact with anybody after that. We had no other contact with Lindell’s people, except for non-technical things, like people arranging the lunch, or the PR flack who wanted to take a video of us cyberexperts confirming the “pcaps”. The PR flack was confused when we told him there were no “pcaps”.

The point is that nobody on Lindell’s team knew what was going on. Nobody on his team knows for certain which files were given to cyberexperts. Nobody on his team really knows what those files contain.

Given this fact, Lindell really had little ability to defend himself in the arbitration panel..

cExtractor and rnx

The decision discussed the large files with names like rnx-000001.bin and the cExtractor program that extracted data from them. These are the files provided by Dennis Montgomery. There were other things in the data on that server, but these two things are at the hard of what’s Lindell believes to be “pcaps”.

The arbitration decision claims “cExtractor was not provided as part of the Contest data”. I’m not sure what this means. The program appeared on the local server alongside the rnx files during the conference. It’s included above in the BitTorrent link. As mentioned above, nobody has an official list of files that were officially part of the Contest data. As far as I can tell, the cExtractor program was part of the Contest data.

The rnx files and the cExtractor program are bizarre and Kafkaesque.

These rnx files were each around 20-gigabytes in size. They contained mostly random data. This may be encrypted data. Proper encryption looks completely random, because if you can find non-random patterns, then you can bypass the encryptions.

Dispersed at random locations within those files were lines of text. Each line started and ended with a recognizable pattern. Extracting all the lines of text produces a 10-mbyte file form the original 20-gbyte file, less than 0.1%.

All that cExtractor did was search the files for those patterns and extract the lines of text.

There’s a question about “encryption”. Each character in the lines of text were rotated by 3 spots (ROT3) in the alphabet. In other words, a string like “shaitan123” would be found in the file as the string “vkdlwdq456”. This is bizarre and no explanation was given for it at the time.

One of Lindell’s people, Doug Frank, testified to the panel:

he said that they put a “simple cipher” in place for at least one file to “separate the men from the boys.” That is, to have participants demonstrate their “sleuthing” skills. Participants would have to find the cypher and de-cypher the data, thus demonstrating their skill.

This ROT3 is probably what he was talking about. It’s known as a Caesar cipher. His explanation for this is still nonsense. I think he’s trying to justify the crazy things Dennis Montgomery was doing. ROT3 isn’t really considered encryption today, just obfuscation. It would be inaccurate to claim that the cExtractor decrypted anything. It just searched the RNX files for lines and text and printed them.

In order to demonstrate what was going on, I wrote my own version of the extraction program: https://github.com/robertdavidgraham/blxtract.

This clearly shows that all Dennis Montgomery gave Lindell was a fake spreadsheet that he then obfuscated with technical slight-of-hand. It certainly fooled Lindell’s cyberguys like Waldron.

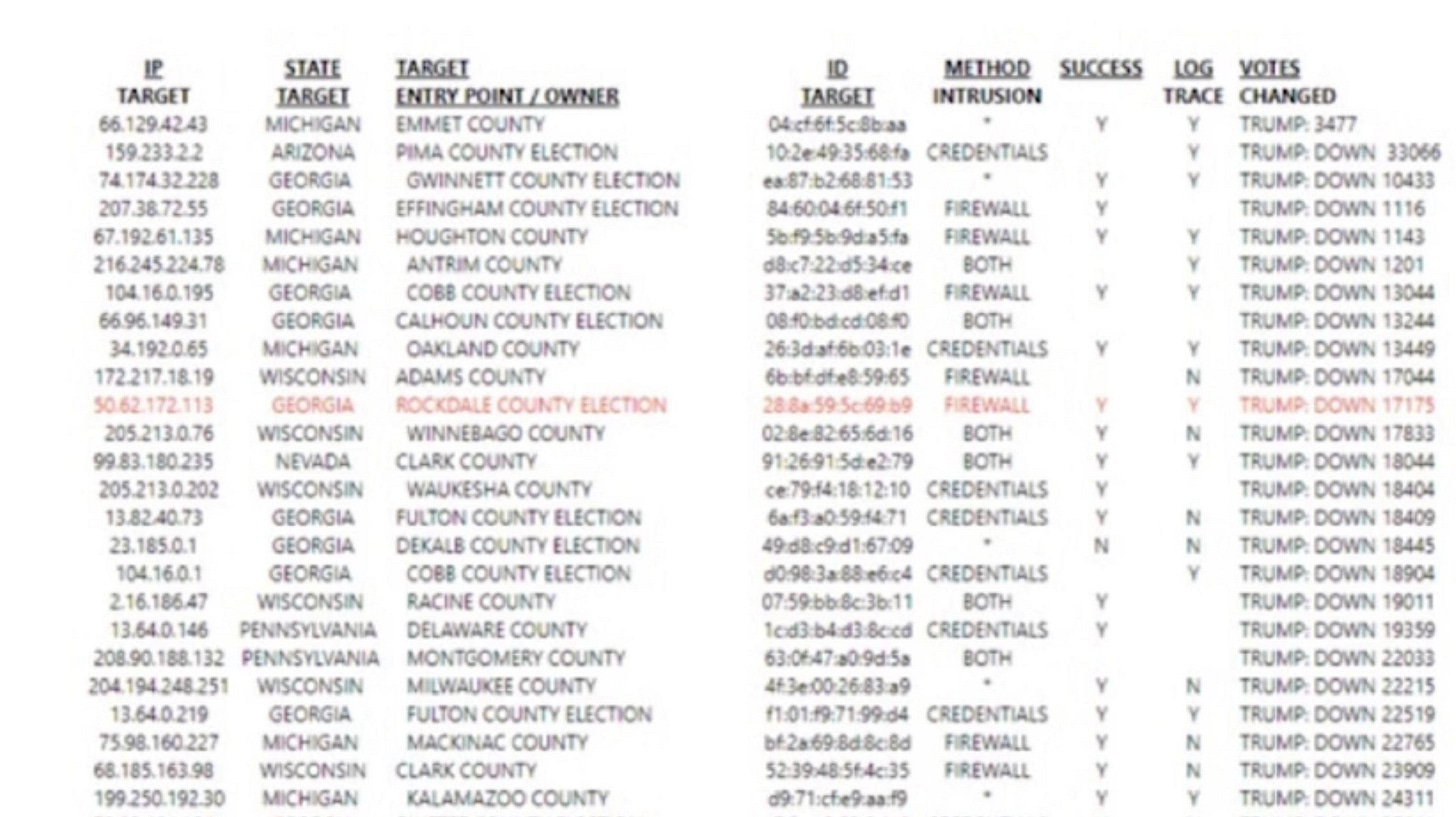

What the data is supposed to show

What appears to have happened is that the Dennis Montgomery created this (fake) spreadsheet and sold it to Lindell for over a million dollars. Montgomery wrapped it up in technical flim-flam, such as creating huge files of random data, inserting each line of the spreadsheet, ROT3 obfuscating it. The hapless Lindell, surrounding himself with non-expert “cyberexperts”, was unable to pierce the ruse.

His original “Absolute Proof” videos show this spreadsheet.

The data he provided at the Cybersymposium just comes back to this same spreadsheet, identifying the attacker and target Internet addresses:

There appears to be nothing else here.

Lindell claims this spreadsheet reflects what happens in the November 2020 election. His contest challenges people to prove it didn’t. That’s the rules of the contest:

1. Overview. Lindell Management, LLC. ("Lindell") has created a contest where participants will participate in a challenge to prove that the data Lindell provides, and represents reflects information from the November 2020 election, unequivocally does NOT reflect information related to the November 2020 election (the "Challenge") .

I still think it’s un-winnable. I don’t see how anybody can unequivocally prove the above screenshots do NOT reflect information related to the November 20202 election. But the panel somehow argument that they don’t.

Conclusion

It’s obvious I should’ve submitted a claim as per the contest rules. Whether or not I think a contest is winnable, the real question is whether the courts or arbitration panels would find such things winnable. Lindell’s contest was obviously fraudulent, his claims obviously unsubstantiated, so there’s legal wiggleroom here.